The day that Diego Maradona said goodbye, as his voice cracked, his mind drifted to the mistakes that he had made, the price that he had paid.

In his valedictory moment, he did not seek absolution. All he asked, instead, was that the sport that he had loved and that had adored him in return, the one that he had mastered, the one he had illuminated, the one he lifted into an art, was not tarnished by all that he had done.

The last line of his speech that day – the final time he graced La Bombonera, home of Boca Juniors, the club that held him closest to its heart – became an Argentine aphorism: “La pelota no se mancha,” he told the adoring crowd. The ball does not show the dirt.

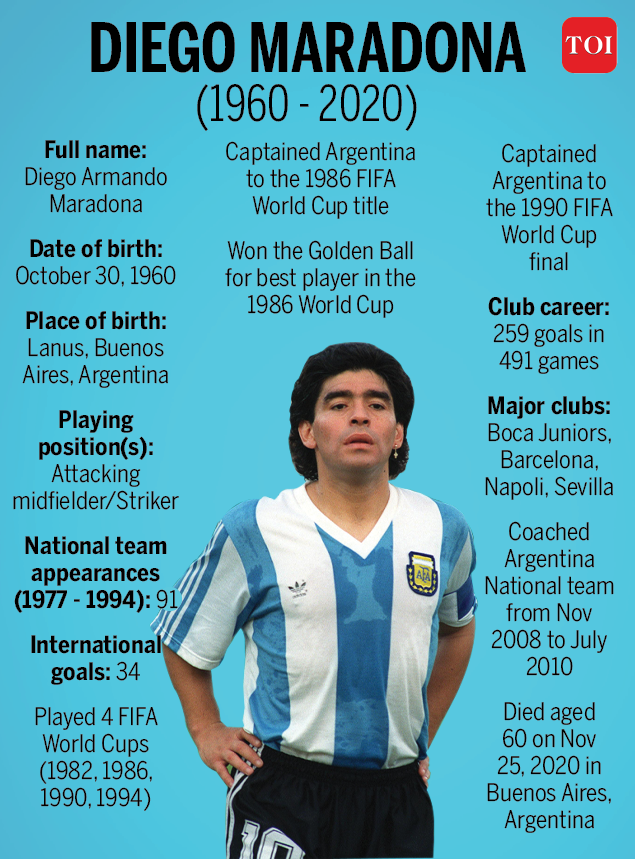

It is certainly possible that Diego Armando Maradona, who died Wednesday at age 60, was the finest soccer player ever to draw breath, though that is a subject of hot and unyielding debate. Less contentious is the idea that no other player has ever inspired such fierce devotion.

There is something approaching a cult in his name in Naples, the overlooked and demeaned port city that he transformed into the centre of the football universe for a few, glorious years at the peak of his career. The city’s mayor on Wednesday suggested the stadium that houses his former club, Napoli, should be renamed for him. That privilege currently falls to St. Paul.

In Argentina, Maradona’s homeland there has long been a church in his honour. For many, Maradona was a quasireligious experience.

He was no straightforward icon. He struggled with drug addiction for decades. He was thrown out of a World Cup in disgrace after testing positive for drugs. Health troubles plagued him, testament to a life of excess. There were allegations of domestic abuse. There were guns and associations with organized crime. The tendency as football reeled from the news of his death, as the eulogies flowed from Lionel Messi (“eternal”) and from Cristiano Ronaldo “a genius”) and from Pelé (“a legend”), was to strike his demons from memory out of respect, out of affection. And yet without mention of those troubles, Maradona’s story is not cleansed.

It is contorted.

Those struggles did not improve him as a player. Instead, they would prevent him from achieving all that he might have done.

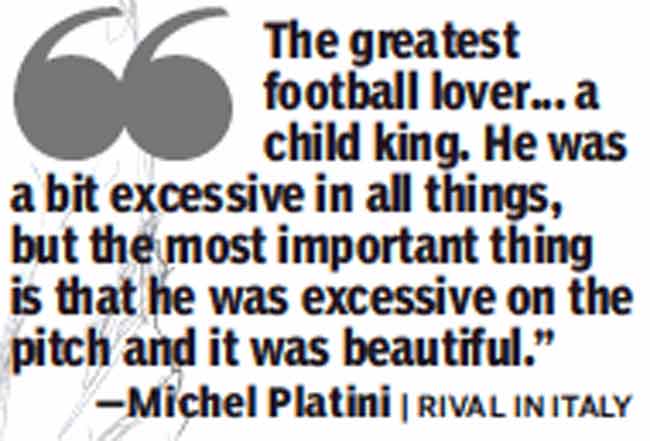

But if the flaws diminished what Maradona was, they burnished what he represented to those who watched him, those who adored him. That such beauty could emerge from such tumult made him mean something more. His darkness sharpened the contours of his light.

Thirty-two years before Maradona was born, the great Argentine writer Borocotó – editor of El Gráfico, the prestigious, trailblazing sports magazine – suggested the country should erect a statue to the so-called pibe: the dustyfaced street kid with the “trickster eyes,” “a mane of hair rebelling against the comb” and the “sparkling gaze” who represented not only Argentina’s football culture, but also its self-image as a nation.

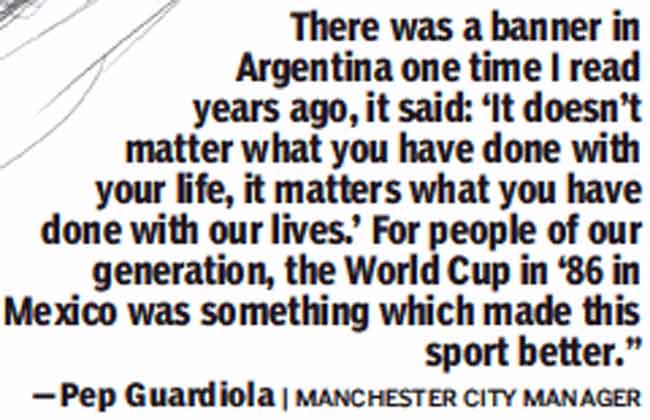

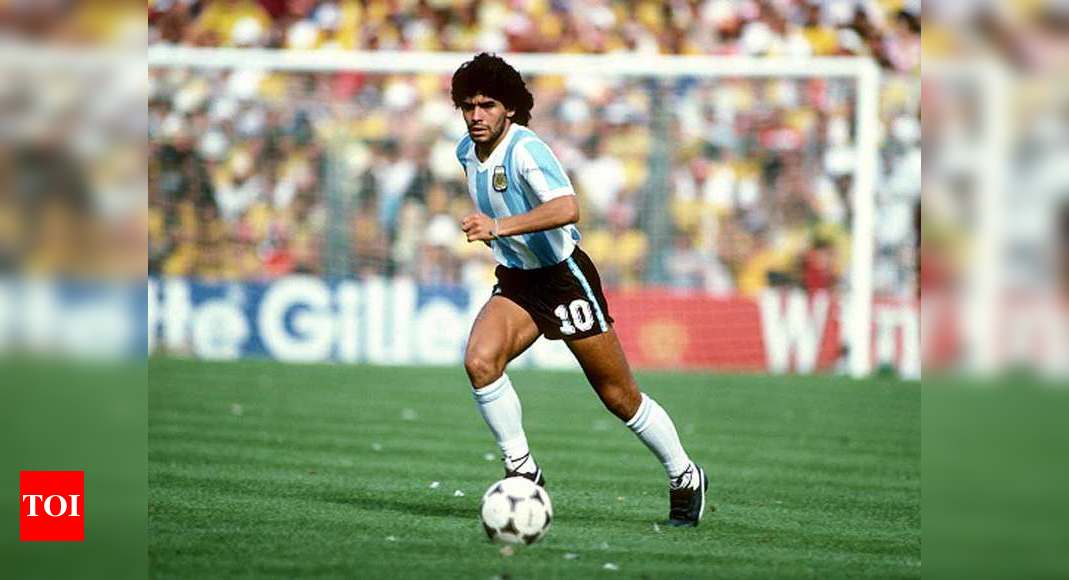

Maradona was the platonic ideal of a pibe, all virtuoso skill and impetuous cunning. All of those iconic images of Maradona are monuments to the spirit of the pibe: leaping high above Peter Shilton, the goal that he would joke – with the “Picaresque laugh” that met Borocotó’s description – was scored by the Hand of God; dancing, a couple of minutes later, through the entire England team to score “the goal of the century,”; facing up to the entire Belgian team.

He was a pibe when he almost single-handedly dragged Argentina to the World Cup in 1986, and back to the final four years later. He was a pibe when he took Napoli to not one, but two Serie A titles. He was a pibe even as he conquered the world. That was his glory, and it was also his downfall.

02:07Diego Maradona: A magician footballer

Maradona himself never made excuses for his missteps. As he told the filmmaker Emir Kusturica in 2008, he held himself responsible for all that he had done. But he knew, too, that at some point a line had to be drawn between Maradona the person and Maradona the player. His legacy as the former is a complex one: a brilliant, troubled individual, one who suffered pain but inflicted it, too, a boy and then a man who crumbled and cracked. But his meaning as the latter is more straightforward. Maradona encapsulated an ideal, he infatuated a nation.

No matter how deep the darkness, it should not be allowed to obscure the light that he brought. “La pelota no se mancha.” The ball does not show the dirt.

More News

‘You cannot point a finger at Ravindra Jadeja like…’: Kevin Pietersen hails CSK all-rounder as an ‘absolute star’ | Cricket News – Times of India

Sprint legend Usain Bolt named T20 World Cup brand ambassador | Cricket News – Times of India

‘India can send three teams to the T20 World Cup’ | Cricket News – Times of India