<!–

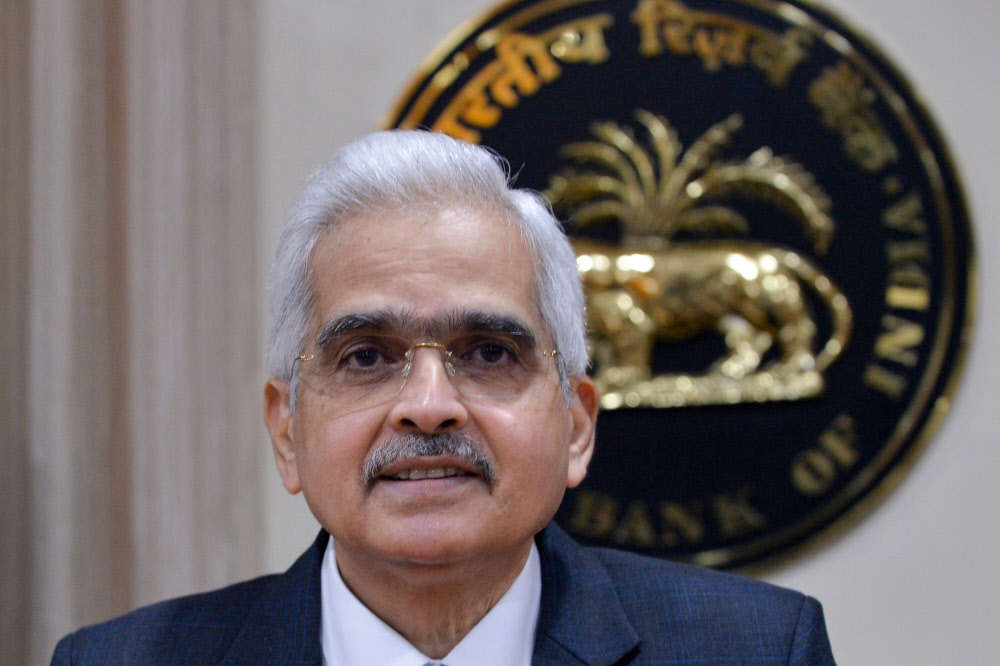

Over the last two weeks, the Opposition is disrupting the Lok Sabha on the grounds of high LPG price and GST on pre-packaged food items as factors behind inflation. And today, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) increased the repo rate by 50 basis points to 5.4%. However, my take on current bout of inflation is different; contribution of LPG and GST to inflation (read, CPI number) are minimal and the hike in repo rate will be less consequential in taming inflation.

From a layman perspective, inflation happens when there is a mismatch between demand and supply of output. Managing inflation is to manage demand-side factors, supply-side factors, or a combination of both, affecting availability of output (GDP). Demand management policy refers to use of fiscal and monetary policy when there is inflation characterised by a positive output gap (difference between demand and supply). Agricultural output gap or the cause of food price inflation can happen because of increase in demand-side factors, or from a reduction in supply of outputs.

Demand-side Factors: Among demand-side factors, consumption expenditure is important. In India, consumption expenditure contributes close to 65% of GDP. Since the start of this millennium, there has been an increase in real income (and hence, consumption) resulting in a shift in preference towards consuming high protein items such as meat, milk and eggs. Advocates of demand-side factors causing inflation believe in this story that increase in food price inflation is because of demand-side factors or higher income resulting from the India growth story.

But consumption of food items cannot move beyond the steady-state level of consumption. This is particularly true for basic cereals and vegetables. Moreover, real wage rate data suggest that there has been a marginal increase in real wage for non-agricultural workers post-2015. For construction workers there has been a fall in real wage rate, particularly post-2019.

Also, last fiscal there has been a reduction in outlay on account of MGNREGA, a dip of 34% in FY 22 compared with FY 21. The rural economy employs 350 million people (around 54% of the total workforce) and contributes nearly half of India’s total GDP. The slow growth in FMCG and two-wheeler sales in rural areas testifies the lack of demand. Additionally, procurement of food grains on account of Minimum Support Price (MSP) has fallen from Rs 2.87 lakh crore in FY 21 to Rs 2.37 lakh crore in FY 22. The factors which may have crank-up demand are missing. Clearly the root cause of inflation is not demand-driven.

Supply-side Factors: There has been a fall in net sown area. As per latest estimate, the net sown area in India is 139.3 million hectares (Annual Report 2021-22, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India). 10 years back this number was 141.1 million hectares.

Technology is also not coming to a rescue. For a long period of time, output per hectare, a common measure of agriculture productivity, remained low in India. For example, in potato farming, the productivity of an Indian farmer is less than half of that of the US, Germany and Netherlands. In the case of rice, it is less than half of that of the US and Egypt, and for wheat, it is less than half of that of the UK and Egypt. Over the last one decade, the annual growth of our agriculture output has been hovering around 3%. With around 50% of India’s agricultural produce still dependent on rainfall, a below-normal or excessive rain impact agricultural production. Lower agricultural produce also means higher fodder prices for livestock, leading to increase in price of meat, eggs, and milk.

Statistics Don’t Lie: Coming back to the comments by the opposition party, let us see if indeed the rise in LPG and pre-packaged food items is fuelling inflation. In India, the consumer price index (CPI) is used as a measure of inflation. Examining the weights of various commodities in the current CPI series indicates that LPG (belonging to Fuel and Light-category) contribute a meagre 6.84%, whereas the Food and Beverages contribute to 45.8% of the total weight. So the inflation, as explained by CPI, is driven more by the rise in price of food and beverages and not LPG.

Within the Food and Beverages category, a large chunk (more than 10%) is contributed by fruits and vegetables whereas the newly added pre-packaged items will have less than 1% weight. In fact, pre-packaged food items weighing more than 25 kg in a single packet would be exempted from GST. So let us concentrate on factors increasing the prices of fruits and vegetables.

In addition to poor agricultural productivity and shrinkage in net sown areas, another factor which is contributing to price rise is climate change. The recent spate of rise in apple, lemon, and tomato prices in the month of June has to do with excessive heat waves in the Northern part of India. The apple growing orchards in the foothills of Himachal Pradesh are fast vanishing. Unseasonal rains and excessive heat damaged production of lemons, mangoes, and tomatoes. Even wheat output has fallen because of excessive heat. Capacity constraints in the form of a lacking cold storage facilities and an imperfect market due to lack of reforms in the APMC Act has added fuel to the fire.

Tailpiece: Since May, RBI has been trying to firefight inflation by raising interest rates. Rate hikes cannot curb inflation when it is not driven by the demand side factors. Fiscal side initiatives such as reforms in the agricultural space and putting in place climate control policies may help.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

<!–

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

–>

END OF ARTICLE

More News

Why business curbs are new weapon in RBI armoury – Times of India

E-tailers start tagging ‘health drinks’ as ‘nutrition drinks’ – Times of India

ICICI blocks 17k cards over glitch – Times of India